Heart Throbbed

A detailed analysis of an issue of Heart Throbs Comics (No. 130: March 1971) has produced a rather stunning revelation: adolescent girls of the 1960s and 70s have somehow survived into adulthood despite a ruthless program of social engineering geared toward the psychic implantation of crippling shame, guilt, and suspicion. This particular issue, which we must assume is relatively representative of the entire Heart Throbs product line, contains four stories of gynocentric romance—each designed to teach young girls that they must never say what they mean or mean what they say. Further analysis indicates that securing a “boy” is to be the supreme objective of a girl’s life, but this must be accomplished through elaborate strategies of secrecy and denial that allow the harmony of daily social life to remain undisturbed. Finally, Heart Throbs would appear to comfort girls that “romance” always works out in the end--but this success will simply “happen” without any actual agency on the part of the girl. Also, it would appear that when girls are sad they frequently run into the woods for a good cry (who knew? I mean, what boys knew this?).

Heart Throb: Case #1

The issue opens strong with “Life Father…Like Daughter!” Cindy and her Mom move to a new town where Cindy’s good looks immediately attract the attention of the local boys. But something is wrong with Cindy—she and Mom remain aloof within the community, and Mom keeps making cryptic comments to Cindy about once again “getting thrown out of town.” Equally puzzling--dad is nowhere to be seen, although the reader suspects that Mom and Cindy’s weekly train trips somehow involve Cindy’s missing father. Secrets abound.

One day, when the locals begin to pry too deeply into her past, Cindy runs off into the woods to cry. There she meets Ted, and before you know it, they’re dating and cutting the rug at a local teen party (where a fruggin’ beatnik helpfully notes that Cindy actually looks “relaxed” for a change). But when Cindy meets Ted’s parents a few weeks later, she is so overwhelmed by the guilt of her secret that she again runs off into the woods to cry. Ted chases after and convinces her to confess her secret shame: Cindy’s missing father lives in a mental institution! But that changes nothing for Ted, and he assures Cindy his parents will feel the same. Dad, after all, is the President of the University’s Board of Trustees, and prides himself on having overcome the “generation gap.”

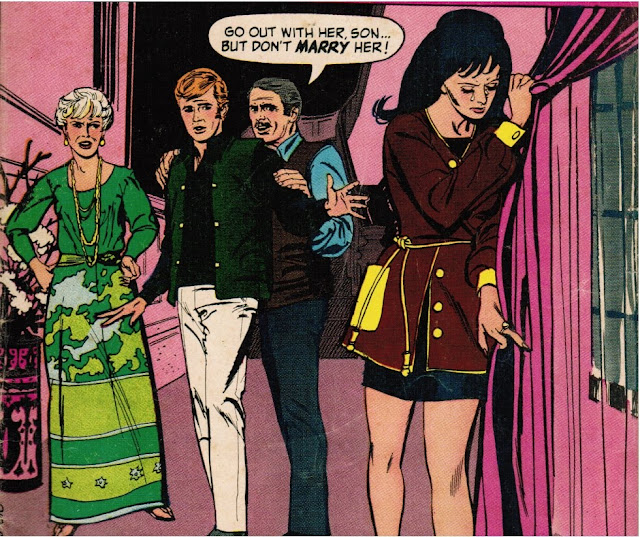

For a while it seems like Ted’s parents really don’t care; in fact, they seem almost overly supportive of Cindy’s “burden.” But that all changes when Ted and Cindy announce their engagement. Now Ted’s parents spring into action to break up the couple--their son simply cannot be allowed to marry into a family with a history of insanity. And then Cindy’s mom lays another bombshell on her—Cindy can never have children because her father’s insanity is hereditary!

Mom suggests they take a long trip to Europe to forget about Ted. But in the end Cindy discovers that it was all a plot cooked up by her Mom and Ted’s parents. Afraid she would lose Cindy just after having “lost” her husband, Mom has accepted $5000 from Ted’s parents to get out of town. Ted and Cindy reunite—lecturing their parents on the value of “true love” and then disappearing into the woods to embark on their new life together.

Lessons learned: (1). Mental illness is so shameful that it demands immediate relocation of the entire family; (2). Revealing your secrets will most likely result in secret plots against you; (3). No matter how “progressive” adults seem—they will still fuck you over; (4). All potential relationships must be evaluated through the lens of “reproductive futurism”: (5) Widowed, divorced, and otherwise “separated” moms most likely want you to grow up and be a miserable “spinster.”

Heart Throb: Case #2

In “Guilty Heart,” Pam dares her cousin Roy to dive from the high-board at the local swimming pool. Pam’s best friend Enid (who is in love with Roy) is frightened and doesn’t want Roy to do it. But Roy goes ahead anyway and promptly breaks his neck. Roy is dead. Enid is devastated and Pam is overwhelmed with guilt (not so much for “killing” her cousin as for ruining Enid’s romance).

A year or so passes and things gradually return to normal. One night a cute guy named Charles seeks Pam out at a party—he’s a young hotshot newspaper editor who has been told by Pam’s old schoolmate that he would really like Pam. And he does! They have a great date and make plans for many more. But then the next day, when Pam and Enid are at the malt shop, Pam notices that Enid finally seems to be getting over the tragic loss of Roy. After hearing about Charles, Enid admits he sounds great. And then the “guilty heart” kicks in. If Enid sees me with a great new boy, Pam reasons, she will slip back into depression. Solution: Pam must renounce Charles and set him up with Enid instead.

Before you know it, everyone in town is saying Charles and Enid are “almost engaged.” Pam passes her time in the woods crying and writing Charles’ name in the dirt with a stick. Finally, she reluctantly accepts an invitation to a BBQ pool party. Looking up at the diving board, she sees Charles about to make the same dive that killed Roy! She screams out for Charles to stop and then promptly faints. When she wakes up, she finds herself once again in Charles’ arms—her spontaneous cry of fear has proven to all that she still loves Charles, and Charles is still in love with Pam. Enid, on the other hand, is doubly screwed and will now probably end up with a gut full of bourbon and Seconal (although, thankfully, Heart Throbs leaves this to our imagination).

Before you know it, everyone in town is saying Charles and Enid are “almost engaged.” Pam passes her time in the woods crying and writing Charles’ name in the dirt with a stick. Finally, she reluctantly accepts an invitation to a BBQ pool party. Looking up at the diving board, she sees Charles about to make the same dive that killed Roy! She screams out for Charles to stop and then promptly faints. When she wakes up, she finds herself once again in Charles’ arms—her spontaneous cry of fear has proven to all that she still loves Charles, and Charles is still in love with Pam. Enid, on the other hand, is doubly screwed and will now probably end up with a gut full of bourbon and Seconal (although, thankfully, Heart Throbs leaves this to our imagination).

Lessons learned: (1). Girls are mentally responsible for the stupid stunts performed by moronic teenage boys; (2). Boys are so dumb and unaware that girls can trade them like marbles; (3). If you “kill” your BFF’s boyfriend, you owe her a replacement, even if the entire triangle is based on a foundation of secrets and lies; (4). “True boy-love” is more important than the emotional stability and mental welfare of all your girlfriends; (5). Many comic book writers of the 1970s have seen Vertigo.

Lessons learned: (1). Girls are mentally responsible for the stupid stunts performed by moronic teenage boys; (2). Boys are so dumb and unaware that girls can trade them like marbles; (3). If you “kill” your BFF’s boyfriend, you owe her a replacement, even if the entire triangle is based on a foundation of secrets and lies; (4). “True boy-love” is more important than the emotional stability and mental welfare of all your girlfriends; (5). Many comic book writers of the 1970s have seen Vertigo.

Heart Throb: Case #3

Heart Throb: Case #3

Story three (“My Heart, My Enemy!”) explores that special bond between sisters. Phyllis is about to go out with Phil on her very first date. That’s fine, says her older sister Nina, so long as Phyllis remembers that Phil will inevitably dump her just as soon as he spots someone more attractive. After all, that’s what happened to Nina with her first boyfriend. The best plan, Nina says, is to dump him first and then play the field—never getting too attached to any one guy. That’s what Nina does, and she couldn’t be happier (or so it seems). So, even though Phil seems like a swell guy who really likes Phyllis, she tells him to back off after their first and only date. Phyllis tries to date another guy, but all she can think about is Phil. Why did she listen to Nina? She goes out into the woods to cry by the pond. Happily, Phil finds her there and professes his love. Nina, we presume, will continue sleeping with every guy in town until she is a bitter old crone sautéing in her own bile.

Lessons learned: (1). At a certain age your older sister will begin to hate you because you now represent competition for boy attention; (2). Boys will always ditch Jennifer Aniston for Angelina Jolie; (3). If you do decide to date several guys, it is probably a symptom of earlier emotional trauma--"good" girls deserve love, "bad" girls are emotionally dysfunctional.

Heart Throb: Case #4

Happily, after so much crying in the woods, Heart Throbs comes to an end with a comic piece about the hazards of computer dating—a practice apparently already in wide enough circulation by the early 1970s to motivate a plot for adolescents. Girl runs her own dating agency. She interviews a cute guy and then instructs her “computer expert” (who looks more like a retired Vegas blackjack dealer) to manipulate the cute guy’s card so that it matches her own. The cute guy sure seems surprised when his computer-selected date turns out to be the girl who runs the dating agency. But then the cute boy has a confession: he also asked the old “computer expert” to manipulate the data so that they would be a match. At first this seems great, but then the girl—remembering she has a business to run—decides she has to reprimand her computer expert for allowing a customer to manipulate him so easily. But the computer expert has the last laugh—curious that both boy and girl wanted him to manipulate the data for a date, he went ahead and ran their cards “as is.” Turns out they were a “perfect match” already—no data shenanigans necessary.

Lessons learned: (1) True love can be calculated and verified empirically; (2). Relationships founded on subterfuge and lying are nevertheless still worth having; 3). There are higher forces in the universe that make sure that everything will work out in the end, especially when it comes to “true love.”

All in all it was a chilling read, like science-fiction from a parallel universe that seems strangely familiar yet at the same time wholly alien. Were all the girls in my junior high school really running into the woods every other day to cry? What did the city girls do when there were no woods nearby for emotional refuge? Did or do girls really hate each other this much? On behalf of patriarchy, I apologize to any and all women who were hopelessly scarred by consuming such horseshit. I think I finally have some minor insight now into what creates a world-class “cutter.”

Heart Throb: Case #1

The issue opens strong with “Life Father…Like Daughter!” Cindy and her Mom move to a new town where Cindy’s good looks immediately attract the attention of the local boys. But something is wrong with Cindy—she and Mom remain aloof within the community, and Mom keeps making cryptic comments to Cindy about once again “getting thrown out of town.” Equally puzzling--dad is nowhere to be seen, although the reader suspects that Mom and Cindy’s weekly train trips somehow involve Cindy’s missing father. Secrets abound.

One day, when the locals begin to pry too deeply into her past, Cindy runs off into the woods to cry. There she meets Ted, and before you know it, they’re dating and cutting the rug at a local teen party (where a fruggin’ beatnik helpfully notes that Cindy actually looks “relaxed” for a change). But when Cindy meets Ted’s parents a few weeks later, she is so overwhelmed by the guilt of her secret that she again runs off into the woods to cry. Ted chases after and convinces her to confess her secret shame: Cindy’s missing father lives in a mental institution! But that changes nothing for Ted, and he assures Cindy his parents will feel the same. Dad, after all, is the President of the University’s Board of Trustees, and prides himself on having overcome the “generation gap.”

For a while it seems like Ted’s parents really don’t care; in fact, they seem almost overly supportive of Cindy’s “burden.” But that all changes when Ted and Cindy announce their engagement. Now Ted’s parents spring into action to break up the couple--their son simply cannot be allowed to marry into a family with a history of insanity. And then Cindy’s mom lays another bombshell on her—Cindy can never have children because her father’s insanity is hereditary!

Mom suggests they take a long trip to Europe to forget about Ted. But in the end Cindy discovers that it was all a plot cooked up by her Mom and Ted’s parents. Afraid she would lose Cindy just after having “lost” her husband, Mom has accepted $5000 from Ted’s parents to get out of town. Ted and Cindy reunite—lecturing their parents on the value of “true love” and then disappearing into the woods to embark on their new life together.

Lessons learned: (1). Mental illness is so shameful that it demands immediate relocation of the entire family; (2). Revealing your secrets will most likely result in secret plots against you; (3). No matter how “progressive” adults seem—they will still fuck you over; (4). All potential relationships must be evaluated through the lens of “reproductive futurism”: (5) Widowed, divorced, and otherwise “separated” moms most likely want you to grow up and be a miserable “spinster.”

Heart Throb: Case #2

In “Guilty Heart,” Pam dares her cousin Roy to dive from the high-board at the local swimming pool. Pam’s best friend Enid (who is in love with Roy) is frightened and doesn’t want Roy to do it. But Roy goes ahead anyway and promptly breaks his neck. Roy is dead. Enid is devastated and Pam is overwhelmed with guilt (not so much for “killing” her cousin as for ruining Enid’s romance).

A year or so passes and things gradually return to normal. One night a cute guy named Charles seeks Pam out at a party—he’s a young hotshot newspaper editor who has been told by Pam’s old schoolmate that he would really like Pam. And he does! They have a great date and make plans for many more. But then the next day, when Pam and Enid are at the malt shop, Pam notices that Enid finally seems to be getting over the tragic loss of Roy. After hearing about Charles, Enid admits he sounds great. And then the “guilty heart” kicks in. If Enid sees me with a great new boy, Pam reasons, she will slip back into depression. Solution: Pam must renounce Charles and set him up with Enid instead.

Before you know it, everyone in town is saying Charles and Enid are “almost engaged.” Pam passes her time in the woods crying and writing Charles’ name in the dirt with a stick. Finally, she reluctantly accepts an invitation to a BBQ pool party. Looking up at the diving board, she sees Charles about to make the same dive that killed Roy! She screams out for Charles to stop and then promptly faints. When she wakes up, she finds herself once again in Charles’ arms—her spontaneous cry of fear has proven to all that she still loves Charles, and Charles is still in love with Pam. Enid, on the other hand, is doubly screwed and will now probably end up with a gut full of bourbon and Seconal (although, thankfully, Heart Throbs leaves this to our imagination).

Before you know it, everyone in town is saying Charles and Enid are “almost engaged.” Pam passes her time in the woods crying and writing Charles’ name in the dirt with a stick. Finally, she reluctantly accepts an invitation to a BBQ pool party. Looking up at the diving board, she sees Charles about to make the same dive that killed Roy! She screams out for Charles to stop and then promptly faints. When she wakes up, she finds herself once again in Charles’ arms—her spontaneous cry of fear has proven to all that she still loves Charles, and Charles is still in love with Pam. Enid, on the other hand, is doubly screwed and will now probably end up with a gut full of bourbon and Seconal (although, thankfully, Heart Throbs leaves this to our imagination).  Lessons learned: (1). Girls are mentally responsible for the stupid stunts performed by moronic teenage boys; (2). Boys are so dumb and unaware that girls can trade them like marbles; (3). If you “kill” your BFF’s boyfriend, you owe her a replacement, even if the entire triangle is based on a foundation of secrets and lies; (4). “True boy-love” is more important than the emotional stability and mental welfare of all your girlfriends; (5). Many comic book writers of the 1970s have seen Vertigo.

Lessons learned: (1). Girls are mentally responsible for the stupid stunts performed by moronic teenage boys; (2). Boys are so dumb and unaware that girls can trade them like marbles; (3). If you “kill” your BFF’s boyfriend, you owe her a replacement, even if the entire triangle is based on a foundation of secrets and lies; (4). “True boy-love” is more important than the emotional stability and mental welfare of all your girlfriends; (5). Many comic book writers of the 1970s have seen Vertigo. Heart Throb: Case #3

Heart Throb: Case #3Story three (“My Heart, My Enemy!”) explores that special bond between sisters. Phyllis is about to go out with Phil on her very first date. That’s fine, says her older sister Nina, so long as Phyllis remembers that Phil will inevitably dump her just as soon as he spots someone more attractive. After all, that’s what happened to Nina with her first boyfriend. The best plan, Nina says, is to dump him first and then play the field—never getting too attached to any one guy. That’s what Nina does, and she couldn’t be happier (or so it seems). So, even though Phil seems like a swell guy who really likes Phyllis, she tells him to back off after their first and only date. Phyllis tries to date another guy, but all she can think about is Phil. Why did she listen to Nina? She goes out into the woods to cry by the pond. Happily, Phil finds her there and professes his love. Nina, we presume, will continue sleeping with every guy in town until she is a bitter old crone sautéing in her own bile.

Lessons learned: (1). At a certain age your older sister will begin to hate you because you now represent competition for boy attention; (2). Boys will always ditch Jennifer Aniston for Angelina Jolie; (3). If you do decide to date several guys, it is probably a symptom of earlier emotional trauma--"good" girls deserve love, "bad" girls are emotionally dysfunctional.

Heart Throb: Case #4

Happily, after so much crying in the woods, Heart Throbs comes to an end with a comic piece about the hazards of computer dating—a practice apparently already in wide enough circulation by the early 1970s to motivate a plot for adolescents. Girl runs her own dating agency. She interviews a cute guy and then instructs her “computer expert” (who looks more like a retired Vegas blackjack dealer) to manipulate the cute guy’s card so that it matches her own. The cute guy sure seems surprised when his computer-selected date turns out to be the girl who runs the dating agency. But then the cute boy has a confession: he also asked the old “computer expert” to manipulate the data so that they would be a match. At first this seems great, but then the girl—remembering she has a business to run—decides she has to reprimand her computer expert for allowing a customer to manipulate him so easily. But the computer expert has the last laugh—curious that both boy and girl wanted him to manipulate the data for a date, he went ahead and ran their cards “as is.” Turns out they were a “perfect match” already—no data shenanigans necessary.

Lessons learned: (1) True love can be calculated and verified empirically; (2). Relationships founded on subterfuge and lying are nevertheless still worth having; 3). There are higher forces in the universe that make sure that everything will work out in the end, especially when it comes to “true love.”

All in all it was a chilling read, like science-fiction from a parallel universe that seems strangely familiar yet at the same time wholly alien. Were all the girls in my junior high school really running into the woods every other day to cry? What did the city girls do when there were no woods nearby for emotional refuge? Did or do girls really hate each other this much? On behalf of patriarchy, I apologize to any and all women who were hopelessly scarred by consuming such horseshit. I think I finally have some minor insight now into what creates a world-class “cutter.”