Oscar Wars: Past, Present, and Future

Somehow I actually saw 5 of the films nominated for Best Picture this year in the Oscars, which is a new personal record I think, considering this is typically the category that proves the most painful and insulting to anyone who once held great hope for the artistic potential of the cinema. Yes, it’s become very predictable to complain about Oscar’s exceptionally dreadful taste in filmmaking, but consider some of the movies the Academy has deemed the epitome of artistic excellence over the past few years: Crash (2005), Million Dollar Baby (2004), A Beautiful Mind (2001), American Beauty (1999), Titanic (1997), and The English Patient (1996). Honestly, if I had 15 or so hours to spare, I’d rather prep for a colonoscopy than sit through this parade of humorless bombast again.

I find the Oscars ceremony to be the one thing on television I simply cannot watch anymore, not even through the lens of camp, snark, or nihilistic irony. Sure, it was kind of funny when Kramer vs. Kramer beat Apocalypse Now in 1979, but when Ordinary People beat Raging Bull the very next year, you had the sense that very dark days were ahead for the art of the motion picture. And looking at the winners over the past thirty years, it has been a bit like the International Pastry Society awarding top prize to the same soggy twinkie over and over again (actually, this probably isn’t the correct analogy inasmuch as a “twinkie” implies a competent genre film with no higher ambition other than to spike your blood sugar for a couple of a hours. Perhaps the more apt “winner” in this example would be a frozen Sara Lee cheesecake purportedly made from a “blue ribbon” recipe handed down from a Chef at Versailles, but which in fact is only a pan of lard and corn syrup injected with those Technicolor dyes manufactured alongside the New Jersey Turnpike).

I guess there is still a residual sort of sick humor to be had in watching the Inside Hollywood Entertainment Access Starf#@ker Tonight twits engaging in the usual red carpet blather, praising celebrities for their generous work on behalf of Haiti and then empathizing, in the same breath, about just how hard it must have been standing in front of a blue screen for four or five hours a day while P.A.’s wrangled their lattes and blackberries between takes. But that type of humor is really only funny when both you and the world are for the most part dead inside.

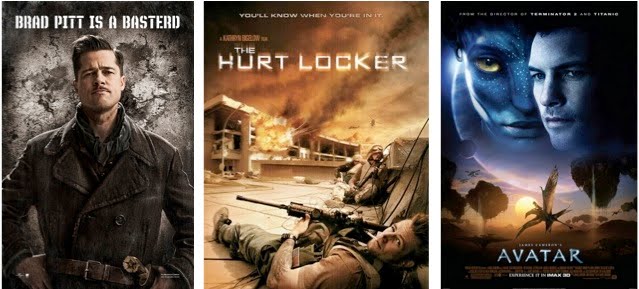

So while typically avoiding the nominated films, more by intuition than design, I did happen to see this year’s big winner, The Hurt Locker. First of all, how is it that Hollywood rather quietly gave us a military version of “A Christmas Carol” this year? Along with the “ghost of warfare present” in The Hurt Locker, we have the “ghost of warfare past” in Inglorious Basterds and the “ghost of warfare future” in Avatar. And while they may seem to be creatures of radically different genres, the war and history theme actually brings out some interesting points of contact in terms of the politics of style.

Let’s start with the winner, Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker. On Larry King of all places, I heard Bigelow promoting the meme that has come to define this project, especially as the bottom-feeding toadies working at the other studio marketing departments began stoking the anticipated backlash campaign against the film. Bigelow maintained the goal of the movie was to avoid the “politics” of the Iraq war and simply tell the story of the incredible work done by these brave soldiers. The Hurt Locker thus opts for the current style of “non-style” characterizing contemporary films that do not want to appear as though they have been dramatized (i.e. picking up scenes in the middle of action or movement, as if a documentarian just raced in with the camera; using moments of “poor” cinematography as a means of restricting narration; the copious use of high-angle extreme long shots to set or reiterate narrative space, in this case mimicking an institutional camera of some sort barred from closer access). It’s not quite a pseudo-verite approach (like the vomit-launcher that is Cloverfield) in that Bigelow frequently locks down and even uses good old eyeline matches to maintain clarity within a scene Of course the “art” of this style resides in its very invisibility—not so much in the classical Hollywood sense of smooth and seemingly sourceless narration—but in matching the look/pace/transitions of the diegesis to those media conventions already most familiar in “seeing” that world (and, alas, even here there is the obligatory running away from an explosion shot--although I guess this is the one film that actually deserves to have this particular blocking in the arsenal).

As for there being no “politics” in The Hurt Locker, that’s quite another matter. In Hollywood, of course, the absence of “politics” means Sean Penn doesn’t roll up in a Humvee to give a canned speech about “blood for oil.” But meticulously creating a sense of non-style is obviously its own form of political intervention, inasmuch as one is promising the audience unfiltered access to the reality of modern warfare; or, as the film’s tagline puts it: “You'll Know When You're in It” (which obviously could have also been the tagline for Avatar).

And then there’s that sad, pathetic, crippled cat hobbling across the streets of Baghdad. Remember him? Hopping around on three legs while holding aloft his little injured paw? Later we see a bedraggled orange tabby prowling the perimeter of a garbage pile. Sure, there are no politics in The Hurt Locker. All I know is that any decent American wouldn’t let an adorable cat wander around injured like that. I’d take him to the vet and make sure he found a good home. What kind of culture lets sweet little cats live such desperate lives?! Let them blow each other up, what do I care!

One final “political” statement: positing that the engine of war runs on a high-octane mix of adrenaline and testosterone is hardly a neutral observation (and given Bigelow’s work in Point Break and Strange Days, perhaps she is the first auteur of the bloodstream). The film might have done more here to implicate our need to experience a Wargasm, safe in the theater or on the couch watching CNN. After all, seeing Sgt. James back stateside buying cereal, cleaning out wet gutters, and making small-talk with the wife, who doesn’t want him back on the first plane to Baghdad? And shouldn't we be made to feel somewhat creepy for that?

As for the "ghost of warfare past," we have Inglorious Basterds, and as one would expect, it is the most explicitly self-conscious about the relationship between film and battle, maybe even a little too self-conscious. Before seeing the film, I read a number of critics perplexed as to whether or not this was Tarantino’s “masterpiece.” Maybe I’m a bit old fashioned, but it seems to me if critics are still in search of a masterpiece high, they should know it when they see/feel it. If you shoot-up top-grade heroin, you shouldn’t have to stop and wonder if it might actually only be chopped up dog tranquilizers.

Masterpiece fishing aside, Inglorious Basterds activates the same basic enigma at the heart of all of Tarantino’s work so far: is this a playfully disruptive genre hybrid (aka "mash-up"), or is it two or three exquisitely crafted interrogation scenes surrounded by a series of narrative dead-ends and gratuitous stylistic flourishes? Hugo Stiglitz, for example. The psycho Nazi-hating Nazi appears at first to rate his own freeze-frame/title card overlay and quick back-story montage, only to then virtually disappear until his completely functionless death at mid-picture. Is Stiglitz (and “the Bear Jew,” etc.) an attempt to bait the Dirty Dozen hook only to subvert the formula by quickly abandoning any ongoing investment in the ragtag unit in favor of the doubled A-line rendez-vous at the Nazi-nitrate BBQ? Or did Tarantino just lose interest in this character/device? Or, in another possibility, is there perhaps another 20 minutes of Stiglitz on the cutting room floor? Not that “unity” is or should be a concern in Tarantino’s work, but still, the digressive marginalia framing the otherwise conventional construction of the film’s key scenes returns us to one of the most haunting questions of contemporary cinematic poetics: Why are the three segments in Pulp Fiction presented out of order? No, really, why?

On Tarantino’s side, there is the wonderfully daft and seemingly deliberate strategy of having two “caper” plots that never really run into one another, as well as the inspired choice of resurrecting the haunting theme from the otherwise wholly disposable 1983 remake of Cat People as this film’s obligatory jukebox reference. Which again gets us to the heart of the QT aesthetic. Shosanna puts on make-up as David Bowie sings “See these eyes so green…” in a story that is indeed about “putting out the fire” (of Nazism) with the “gasoline” of cinema (or at least its old nitrate prints). Is this a brilliant recognition that all historical signification ultimately dissolves into a pastiche of relativistic quotations; or is it instead the kind of unexamined kitsch skewered so perfectly in the YouTube cult for “literal videos?” I used to think we were heading toward some sort of resolution of this divide in Tarantino’s career—but by now it should be clear that this is how all of the films will be, forever and always.

Cinephiles can certainly appreciate the fantasy of film culture defeating the Nazi menace, although I guess such an approach risks elevating the crimes against UFA over those of the Holocaust (using genocide as an excuse to remake I Spit on Your Grave is a pretty dicey move, especially when you can't tell if Shosanna is mad because the Nazis killed her family or because they forced her to show Leni Riefenstahl movies). On the ethics of history front, I guess the jury will be out until I read my first undergraduate term paper claiming Hitler was shot up like a bad wedding cake during the Paris premiere of Nation’s Pride (and this isn’t a far-fetched scenario, having once witnessed a student claim World War II began when Germany bombed the Japanese at Pearl Harbor!). At that particular moment, I will be happy just to give up and let Cameron, Bay, and an army of Disney Imagineers supervise our collective cultural memory until the melting ice caps flood the last remaining ProTools station.

Oh yeah, Cameron…the "ghost of warfare future," Avatar. I’ve already thought about the blue people as much as I can stand this year, so I’ll keep this short. If Bigelow’s war ghost is phantom objectivity and Tarantino’s specter is an aesthetic that can not leave behind the mortal coil of 90s postmodernity, Cameon’s Avatar gives us that promised future world where warfare and filmmaking no longer really involve humans at all, both becoming virtual enterprises that, even though they burn through mountains of very real money, ultimately happen in an elsewhere that is only intermittently compelling.

But lest we think the “posthuman” era has really begun, consider what may well have been the most riveting story line involving the Oscars this year, on or off the screen: the “war” between Bigelow and Cameron as rival directors and divorcees. The Huffington Post, currently our most reliable index as to the concerns of the Floridean creative class, ran innumerable stories leading up to the Oscars fantasizing about Bigelow’s anticipated humiliation of her Ex (including a “real time” update during the ceremony alerting us that Bigelow’s party had been given better seats than Cameron). Here was a drama people could really relate to: the "little film that could" vs. Cameron’s Icarus-like intervention into the global economy; dumpee vs. dumper, man vs. woman, etc. In the end, this is perhaps Hollywood’s most important function today, generating celebrities as “avatars,” not in some ridiculous paint-box parable about imperialism, but on the much more “real” stage of our still monkey-like emotional range. Or as Huffpo relayed it in a headline more stinging than "Saigon Falls:"

I find the Oscars ceremony to be the one thing on television I simply cannot watch anymore, not even through the lens of camp, snark, or nihilistic irony. Sure, it was kind of funny when Kramer vs. Kramer beat Apocalypse Now in 1979, but when Ordinary People beat Raging Bull the very next year, you had the sense that very dark days were ahead for the art of the motion picture. And looking at the winners over the past thirty years, it has been a bit like the International Pastry Society awarding top prize to the same soggy twinkie over and over again (actually, this probably isn’t the correct analogy inasmuch as a “twinkie” implies a competent genre film with no higher ambition other than to spike your blood sugar for a couple of a hours. Perhaps the more apt “winner” in this example would be a frozen Sara Lee cheesecake purportedly made from a “blue ribbon” recipe handed down from a Chef at Versailles, but which in fact is only a pan of lard and corn syrup injected with those Technicolor dyes manufactured alongside the New Jersey Turnpike).

I guess there is still a residual sort of sick humor to be had in watching the Inside Hollywood Entertainment Access Starf#@ker Tonight twits engaging in the usual red carpet blather, praising celebrities for their generous work on behalf of Haiti and then empathizing, in the same breath, about just how hard it must have been standing in front of a blue screen for four or five hours a day while P.A.’s wrangled their lattes and blackberries between takes. But that type of humor is really only funny when both you and the world are for the most part dead inside.

So while typically avoiding the nominated films, more by intuition than design, I did happen to see this year’s big winner, The Hurt Locker. First of all, how is it that Hollywood rather quietly gave us a military version of “A Christmas Carol” this year? Along with the “ghost of warfare present” in The Hurt Locker, we have the “ghost of warfare past” in Inglorious Basterds and the “ghost of warfare future” in Avatar. And while they may seem to be creatures of radically different genres, the war and history theme actually brings out some interesting points of contact in terms of the politics of style.

Let’s start with the winner, Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker. On Larry King of all places, I heard Bigelow promoting the meme that has come to define this project, especially as the bottom-feeding toadies working at the other studio marketing departments began stoking the anticipated backlash campaign against the film. Bigelow maintained the goal of the movie was to avoid the “politics” of the Iraq war and simply tell the story of the incredible work done by these brave soldiers. The Hurt Locker thus opts for the current style of “non-style” characterizing contemporary films that do not want to appear as though they have been dramatized (i.e. picking up scenes in the middle of action or movement, as if a documentarian just raced in with the camera; using moments of “poor” cinematography as a means of restricting narration; the copious use of high-angle extreme long shots to set or reiterate narrative space, in this case mimicking an institutional camera of some sort barred from closer access). It’s not quite a pseudo-verite approach (like the vomit-launcher that is Cloverfield) in that Bigelow frequently locks down and even uses good old eyeline matches to maintain clarity within a scene Of course the “art” of this style resides in its very invisibility—not so much in the classical Hollywood sense of smooth and seemingly sourceless narration—but in matching the look/pace/transitions of the diegesis to those media conventions already most familiar in “seeing” that world (and, alas, even here there is the obligatory running away from an explosion shot--although I guess this is the one film that actually deserves to have this particular blocking in the arsenal).

As for there being no “politics” in The Hurt Locker, that’s quite another matter. In Hollywood, of course, the absence of “politics” means Sean Penn doesn’t roll up in a Humvee to give a canned speech about “blood for oil.” But meticulously creating a sense of non-style is obviously its own form of political intervention, inasmuch as one is promising the audience unfiltered access to the reality of modern warfare; or, as the film’s tagline puts it: “You'll Know When You're in It” (which obviously could have also been the tagline for Avatar).

And then there’s that sad, pathetic, crippled cat hobbling across the streets of Baghdad. Remember him? Hopping around on three legs while holding aloft his little injured paw? Later we see a bedraggled orange tabby prowling the perimeter of a garbage pile. Sure, there are no politics in The Hurt Locker. All I know is that any decent American wouldn’t let an adorable cat wander around injured like that. I’d take him to the vet and make sure he found a good home. What kind of culture lets sweet little cats live such desperate lives?! Let them blow each other up, what do I care!

One final “political” statement: positing that the engine of war runs on a high-octane mix of adrenaline and testosterone is hardly a neutral observation (and given Bigelow’s work in Point Break and Strange Days, perhaps she is the first auteur of the bloodstream). The film might have done more here to implicate our need to experience a Wargasm, safe in the theater or on the couch watching CNN. After all, seeing Sgt. James back stateside buying cereal, cleaning out wet gutters, and making small-talk with the wife, who doesn’t want him back on the first plane to Baghdad? And shouldn't we be made to feel somewhat creepy for that?

As for the "ghost of warfare past," we have Inglorious Basterds, and as one would expect, it is the most explicitly self-conscious about the relationship between film and battle, maybe even a little too self-conscious. Before seeing the film, I read a number of critics perplexed as to whether or not this was Tarantino’s “masterpiece.” Maybe I’m a bit old fashioned, but it seems to me if critics are still in search of a masterpiece high, they should know it when they see/feel it. If you shoot-up top-grade heroin, you shouldn’t have to stop and wonder if it might actually only be chopped up dog tranquilizers.

Masterpiece fishing aside, Inglorious Basterds activates the same basic enigma at the heart of all of Tarantino’s work so far: is this a playfully disruptive genre hybrid (aka "mash-up"), or is it two or three exquisitely crafted interrogation scenes surrounded by a series of narrative dead-ends and gratuitous stylistic flourishes? Hugo Stiglitz, for example. The psycho Nazi-hating Nazi appears at first to rate his own freeze-frame/title card overlay and quick back-story montage, only to then virtually disappear until his completely functionless death at mid-picture. Is Stiglitz (and “the Bear Jew,” etc.) an attempt to bait the Dirty Dozen hook only to subvert the formula by quickly abandoning any ongoing investment in the ragtag unit in favor of the doubled A-line rendez-vous at the Nazi-nitrate BBQ? Or did Tarantino just lose interest in this character/device? Or, in another possibility, is there perhaps another 20 minutes of Stiglitz on the cutting room floor? Not that “unity” is or should be a concern in Tarantino’s work, but still, the digressive marginalia framing the otherwise conventional construction of the film’s key scenes returns us to one of the most haunting questions of contemporary cinematic poetics: Why are the three segments in Pulp Fiction presented out of order? No, really, why?

On Tarantino’s side, there is the wonderfully daft and seemingly deliberate strategy of having two “caper” plots that never really run into one another, as well as the inspired choice of resurrecting the haunting theme from the otherwise wholly disposable 1983 remake of Cat People as this film’s obligatory jukebox reference. Which again gets us to the heart of the QT aesthetic. Shosanna puts on make-up as David Bowie sings “See these eyes so green…” in a story that is indeed about “putting out the fire” (of Nazism) with the “gasoline” of cinema (or at least its old nitrate prints). Is this a brilliant recognition that all historical signification ultimately dissolves into a pastiche of relativistic quotations; or is it instead the kind of unexamined kitsch skewered so perfectly in the YouTube cult for “literal videos?” I used to think we were heading toward some sort of resolution of this divide in Tarantino’s career—but by now it should be clear that this is how all of the films will be, forever and always.

Cinephiles can certainly appreciate the fantasy of film culture defeating the Nazi menace, although I guess such an approach risks elevating the crimes against UFA over those of the Holocaust (using genocide as an excuse to remake I Spit on Your Grave is a pretty dicey move, especially when you can't tell if Shosanna is mad because the Nazis killed her family or because they forced her to show Leni Riefenstahl movies). On the ethics of history front, I guess the jury will be out until I read my first undergraduate term paper claiming Hitler was shot up like a bad wedding cake during the Paris premiere of Nation’s Pride (and this isn’t a far-fetched scenario, having once witnessed a student claim World War II began when Germany bombed the Japanese at Pearl Harbor!). At that particular moment, I will be happy just to give up and let Cameron, Bay, and an army of Disney Imagineers supervise our collective cultural memory until the melting ice caps flood the last remaining ProTools station.

Oh yeah, Cameron…the "ghost of warfare future," Avatar. I’ve already thought about the blue people as much as I can stand this year, so I’ll keep this short. If Bigelow’s war ghost is phantom objectivity and Tarantino’s specter is an aesthetic that can not leave behind the mortal coil of 90s postmodernity, Cameon’s Avatar gives us that promised future world where warfare and filmmaking no longer really involve humans at all, both becoming virtual enterprises that, even though they burn through mountains of very real money, ultimately happen in an elsewhere that is only intermittently compelling.

But lest we think the “posthuman” era has really begun, consider what may well have been the most riveting story line involving the Oscars this year, on or off the screen: the “war” between Bigelow and Cameron as rival directors and divorcees. The Huffington Post, currently our most reliable index as to the concerns of the Floridean creative class, ran innumerable stories leading up to the Oscars fantasizing about Bigelow’s anticipated humiliation of her Ex (including a “real time” update during the ceremony alerting us that Bigelow’s party had been given better seats than Cameron). Here was a drama people could really relate to: the "little film that could" vs. Cameron’s Icarus-like intervention into the global economy; dumpee vs. dumper, man vs. woman, etc. In the end, this is perhaps Hollywood’s most important function today, generating celebrities as “avatars,” not in some ridiculous paint-box parable about imperialism, but on the much more “real” stage of our still monkey-like emotional range. Or as Huffpo relayed it in a headline more stinging than "Saigon Falls:"