Dead Formats: Roasted Chickens

Hipster enthusiasts of thrift stores are generally motivated by varying combinations of the following possibilities: 1). discovering rare and valuable popular artifacts—first editions, scarce vinyl, obscure memorabilia, etc; 2). uncovering one-of-a-kind art/craft items that evoke some aspect of l’art brut; 3). reconstructing one’s wardrobe around the cultural dominant of the decade immediately preceding that of one’s birth; 4). marveling at the sad and sorry display of consumer cycles that have generated so much crap—much of it still eminently functional--now drained of the exchange/symbolic value that once made these piles of junk new and thus worthwhile.

As for possibility #4, Mike Kelley’s work with appropriated objects and “craft morphologies” explicitly confronted this sense of melancholy, especially his several pieces that integrate orphaned stuffed animals into larger assemblages and installations. More Love Hours than Can Ever Be Repaid (1987) is probably the best known—an abstract collage of craft figures and textures (and for full Midwestern autumnal-quilt effect—a pair of dried corn stalks on the top corners). Kelley has described the work in Bataille-like terms of symbolic exchange—gifts imbued with “love hours” that cannot be repaid—the tyranny of an emotional potlatch, one might say. Hoping to bring an end to the “stuffed toy” phase of his career, Kelley later created the installation Craft Mythology Flow Chart (1991). Hand-made dolls are displayed face-down on a series of non-descript folding-tables, the items grouped for formal inventory and effect in an effort to disrupt the empathetic attachments typically evoked by these mass-engineered vectors of the adorable. On the wall hang photos of the dolls, photographed—as Kelley notes—as if they are anthropological finds (see detail at right). Of course, they also resemble mug-shots, giving the entire layout a forensic/morgue vibe as well (but this is perhaps a reading only enabled by the nation’s intervening obsession with police procedurals).

As for possibility #4, Mike Kelley’s work with appropriated objects and “craft morphologies” explicitly confronted this sense of melancholy, especially his several pieces that integrate orphaned stuffed animals into larger assemblages and installations. More Love Hours than Can Ever Be Repaid (1987) is probably the best known—an abstract collage of craft figures and textures (and for full Midwestern autumnal-quilt effect—a pair of dried corn stalks on the top corners). Kelley has described the work in Bataille-like terms of symbolic exchange—gifts imbued with “love hours” that cannot be repaid—the tyranny of an emotional potlatch, one might say. Hoping to bring an end to the “stuffed toy” phase of his career, Kelley later created the installation Craft Mythology Flow Chart (1991). Hand-made dolls are displayed face-down on a series of non-descript folding-tables, the items grouped for formal inventory and effect in an effort to disrupt the empathetic attachments typically evoked by these mass-engineered vectors of the adorable. On the wall hang photos of the dolls, photographed—as Kelley notes—as if they are anthropological finds (see detail at right). Of course, they also resemble mug-shots, giving the entire layout a forensic/morgue vibe as well (but this is perhaps a reading only enabled by the nation’s intervening obsession with police procedurals).

But even more “anonymous” and overtly corporatized artifacts can carry this affective charge as well. During a recent stop at a thrift store in Kalamazoo, for example, I found a cache of 100+ RCA Selecta Vision discs. As my more tech-savvy colleague informed me, this was RCA’s ill-fated attempt in the early ‘80s to roll out a new format for home entertainment systems—a venture that eventually lost to Betamax and VHS tape. The technical name for the format was the CED (Capacitance Electronic Disc), and they have much more in common with the long-playing record than with the laser-discs they superficially resemble in their packaging. The Wiki-gods report that RCA lost nearly $600 million on the format, which was discontinued when GE and RCA made up and remarried in 1986. As the discs at the Kalamazoo Salvation Army were priced to move, I bought three for the historical record—Disney’s Tron (1982), Saturday Night Live: The Best of Joe Piscopo (1983), and the Kenny Rogers’ film Six-Pack (1982). These choices may seem motivated by the standard-issue ironic detachment haunting post-boomer culture, but I assure you each was selected to maximize the sad connotations of techno-cultural obsolescence. Of the three, Six-Pack may well be the most complex in its layering of melancholia and misery.

Six-Pack on Selecta-Vision is infinitely more depressing than the same film encountered on VHS, Laserdisc, or DVD (if the last object actually exists, God forbid). Perhaps it is a trait unique to media historians, but I’ve always found “extinct” media formats profoundly sad. One can only imagine the original hope invested in these discs as a definitive solution to entropy and thus the key to media immortality. Here was an early attempt to transform the ephemeral experience of the movies quite literally into “records” (the Selecta-Vision system in fact uses a stylus)—the building blocks of an eventual media library. Of course, those who invested in this format were out of luck by 1986, and if they moved over to VHS, they could only watch as a library of videotapes slowly decayed from age and magnetization. Now Blu-Ray is in the process of displacing the DVD (which slayed VHS, obviously) as the new format of eternal transcription—but there really is no end to this anxiety as this obsession with formatting is less about creating a library that might actually outlive its owner than it is about repelling the intruding specter of mortality itself. One has to give credit to the culture industries, which have somehow managed to take a century of wholly disposable media products and invest them with a sense of history, identity, and affect that make millions feel compelled to collect them and repeat—to the grave, apparently—whatever dated pleasures reside within. At this point in history, does anyone who has seen Casablanca (1945) and knows Casablanca really need to own Casablanca? Are episodes of Gilligan’s Island best encountered at random in unexpected moments during the course of life, or are they to be stored on the shelf in “complete seasons,” much like reading-copies of Moby Dick and Ulysses that one keeps on the shelf for a more contemplative rendezvous later in life?

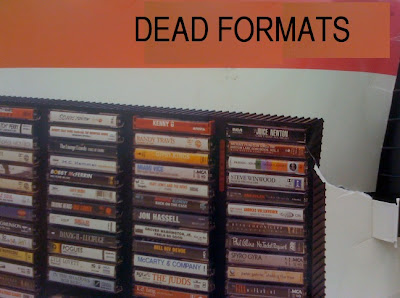

In this respect, owning (and then cataloging and organizing) a body of continually re-formatted films, TV shows, and albums is a ritual that re-affirms the “immortal” flame of one’s taste even as that industrially-inscribed sensibility remains encased in a deteriorating body. As the recent Beatles Box demonstrates, this symptom is particularly pronounced in pop-music fans (myself included), who appear hopelessly caught in a doomed attempt to rekindle whatever feelings of teenage omnipotence have been cathected onto Sgt. Pepper, Exile on Main Street, Never Mind the Bollocks, Nevermind, and whatever other records were considered crucial after I stopped paying attention at the end of the last century. Happily, the Beatles Box may be the last great gesture in this regard as most people under 30 have little to no desire to own music as a material object, having chosen variety and portability over sound fidelity and cover design in circulating the music of the future. Perhaps this will make them less prone to corporatized fetishism, more willing to consume popular texts and then, as with Swiffer pads, be done with them. Already we must celebrate the Net generation’s radical intervention in simply refusing to pay for most mass-produced music, having made the fundamental realization that very few artists are worth shelling out $18.98 (much less the hundreds of dollars needed to replace your copy of Revolver every 15 years). Thrift shelves are now sagging under the weight of discarded CDs—former icons of sonic immortality currently taking their rightful place next to cassettes, 8-tracks, and that most distant and ridiculous of audiophile formats: reel-to-reel tape.

Yes, formats and popular amusements all decay eventually, a process made particularly manifest in the pathos of a Selecta-Vision edition of Six-Pack. Not only is the CED format itself dead, but so too is the cultural imaginary that would produce, enjoy, cherish, and collect a film starring Kenny Rogers. It is a double dead-end of design and desire. For those unfamiliar with Rogers, he first came to prominence in the late ‘60s as the lead singer for Kenny Rogers and the First Edition (“Just Dropped In (to See What Condition My Condition Was In)” was their big hit). He is also known for his 1978 single, “The Gambler,” as well as participating in the landmark “We Are the World” session of 1985 that—at last—brought an end to famine in Africa. At some point he opened a chain of fast-food chicken shacks (Kenny Rogers’ Roasters—most famously a nemesis for Kramer in an episode of Seinfeld). In 1994, a pitcher for the Texas Rangers with the same name threw a perfect game—which no doubt confused many—while in the late ‘90s Rogers became the object of a rather inexplicably brutal series of parodies by Will Sasso on MadTV (see video sidebar). In other words, Rogers is one of those media figures who have proliferated across a range of media (and chicken enterprises) for over forty years—staying within the lexicon of popular reference despite having long ago ceased to generate any cultural product of relevance. Whether we want to or not, we must co-exist in a world that also allows Kenny Rogers inordinate access to mass consciousness, either through music, parody, or poultry distribution.

Six-Pack dates from a period when Rogers—like any efficient proto-convergence franchise--sought to expand beyond the then somewhat limiting domain of country music and capture the larger profits and attention to be found in the movies. The film itself is a confluence of rather unfortunate genres--Smokey the Bandit meets the Bad News Bears—with Rogers playing a NASCAR driver who befriends a motley crew of orphaned children (6 to be exact—hence the title). No doubt this craven calculation in genre/regional hybridization was apparent to many in the period—but with the passing of time, Six Pack becomes an even more pointed reminder of just how low and obvious our expectations are for popular entertainment. Sure, you can say it was a film for kids or the even less demanding audiences that would eventually file into the dinner-theater death compounds of Branson, but that really is no defense at all. If we pretend to befriend the hypothetical viewer who really liked (or likes) Six Pack, that only means we have ceased to struggle against the industry’s vortex of swirling mediocrity--giving up at last on all critical responsibility, holding our noses, and then going down for the last time (perhaps to buy the new Two and a Half Men box-set). Really—and I’m speaking primarily to my fellow media scholars out there—did we put multiple years into a Ph.D. so that we might better understand, defend, and celebrate the pleasures of watching The Ghost Whisperer, having so long ago abandoned any challenge to the world of cynical sentimental crapestry that would create The Ghost Whisperer in the first place?

Six-Pack dates from a period when Rogers—like any efficient proto-convergence franchise--sought to expand beyond the then somewhat limiting domain of country music and capture the larger profits and attention to be found in the movies. The film itself is a confluence of rather unfortunate genres--Smokey the Bandit meets the Bad News Bears—with Rogers playing a NASCAR driver who befriends a motley crew of orphaned children (6 to be exact—hence the title). No doubt this craven calculation in genre/regional hybridization was apparent to many in the period—but with the passing of time, Six Pack becomes an even more pointed reminder of just how low and obvious our expectations are for popular entertainment. Sure, you can say it was a film for kids or the even less demanding audiences that would eventually file into the dinner-theater death compounds of Branson, but that really is no defense at all. If we pretend to befriend the hypothetical viewer who really liked (or likes) Six Pack, that only means we have ceased to struggle against the industry’s vortex of swirling mediocrity--giving up at last on all critical responsibility, holding our noses, and then going down for the last time (perhaps to buy the new Two and a Half Men box-set). Really—and I’m speaking primarily to my fellow media scholars out there—did we put multiple years into a Ph.D. so that we might better understand, defend, and celebrate the pleasures of watching The Ghost Whisperer, having so long ago abandoned any challenge to the world of cynical sentimental crapestry that would create The Ghost Whisperer in the first place?

No doubt popular entertainment is always "great" so long as our technologies remain sexy and our tastes remain blissfully unexamined--but lurking behind this joyous proliferation of rat-holes into which to dump our money, time, and attention is the uncomfortable reality evoked by a Kenny Rogers on Selecta-Vision disc (Selecta! --even the name makes you stupider). Like so much other thrift detritus, it is a reminder of objects and affect now utterly drained of all value--maybe eventually even of all ironic value. Such is the destiny of all that is ill-conceived, poorly made, and obscenely ridiculous--be it a Billy Bass Singing-Fish Plaque or the Blu-Ray copies of Norbit that, even now, move inexorably toward their destiny on the future shelves of Goodwill.

Moreover, Six Pack is a reminder that the oft-celebrated move toward media/narrative convergence--beyond opening multiple paths to consumer ecstasy--is just as often (or actually, at the same time) only a guy and his corporation looking to branch out from shit-kicker radio to get a little taste of the Burt Reynolds market--or singing about poker fights he's never been in--or showing up next to Cyndy Lauper at a charity photo-op to keep his profile/brand relevant--or pretending to have expertise in chicken-roasting that he doubtlessly does not possess. And we do nothing about it. Sad, sad indeed.

Moreover, Six Pack is a reminder that the oft-celebrated move toward media/narrative convergence--beyond opening multiple paths to consumer ecstasy--is just as often (or actually, at the same time) only a guy and his corporation looking to branch out from shit-kicker radio to get a little taste of the Burt Reynolds market--or singing about poker fights he's never been in--or showing up next to Cyndy Lauper at a charity photo-op to keep his profile/brand relevant--or pretending to have expertise in chicken-roasting that he doubtlessly does not possess. And we do nothing about it. Sad, sad indeed.

For more on Mike Kelley's work, see Mike Kelley. ed. by John C. Welchman, Isabelle Graw, Anthony Vidler. New York: Phaidon Press, 1999.

I am indebted to my more tech-savvy colleague Max Dawson for his knowledge of the Selecta-Vision venture.

As for possibility #4, Mike Kelley’s work with appropriated objects and “craft morphologies” explicitly confronted this sense of melancholy, especially his several pieces that integrate orphaned stuffed animals into larger assemblages and installations. More Love Hours than Can Ever Be Repaid (1987) is probably the best known—an abstract collage of craft figures and textures (and for full Midwestern autumnal-quilt effect—a pair of dried corn stalks on the top corners). Kelley has described the work in Bataille-like terms of symbolic exchange—gifts imbued with “love hours” that cannot be repaid—the tyranny of an emotional potlatch, one might say. Hoping to bring an end to the “stuffed toy” phase of his career, Kelley later created the installation Craft Mythology Flow Chart (1991). Hand-made dolls are displayed face-down on a series of non-descript folding-tables, the items grouped for formal inventory and effect in an effort to disrupt the empathetic attachments typically evoked by these mass-engineered vectors of the adorable. On the wall hang photos of the dolls, photographed—as Kelley notes—as if they are anthropological finds (see detail at right). Of course, they also resemble mug-shots, giving the entire layout a forensic/morgue vibe as well (but this is perhaps a reading only enabled by the nation’s intervening obsession with police procedurals).

As for possibility #4, Mike Kelley’s work with appropriated objects and “craft morphologies” explicitly confronted this sense of melancholy, especially his several pieces that integrate orphaned stuffed animals into larger assemblages and installations. More Love Hours than Can Ever Be Repaid (1987) is probably the best known—an abstract collage of craft figures and textures (and for full Midwestern autumnal-quilt effect—a pair of dried corn stalks on the top corners). Kelley has described the work in Bataille-like terms of symbolic exchange—gifts imbued with “love hours” that cannot be repaid—the tyranny of an emotional potlatch, one might say. Hoping to bring an end to the “stuffed toy” phase of his career, Kelley later created the installation Craft Mythology Flow Chart (1991). Hand-made dolls are displayed face-down on a series of non-descript folding-tables, the items grouped for formal inventory and effect in an effort to disrupt the empathetic attachments typically evoked by these mass-engineered vectors of the adorable. On the wall hang photos of the dolls, photographed—as Kelley notes—as if they are anthropological finds (see detail at right). Of course, they also resemble mug-shots, giving the entire layout a forensic/morgue vibe as well (but this is perhaps a reading only enabled by the nation’s intervening obsession with police procedurals). But even more “anonymous” and overtly corporatized artifacts can carry this affective charge as well. During a recent stop at a thrift store in Kalamazoo, for example, I found a cache of 100+ RCA Selecta Vision discs. As my more tech-savvy colleague informed me, this was RCA’s ill-fated attempt in the early ‘80s to roll out a new format for home entertainment systems—a venture that eventually lost to Betamax and VHS tape. The technical name for the format was the CED (Capacitance Electronic Disc), and they have much more in common with the long-playing record than with the laser-discs they superficially resemble in their packaging. The Wiki-gods report that RCA lost nearly $600 million on the format, which was discontinued when GE and RCA made up and remarried in 1986. As the discs at the Kalamazoo Salvation Army were priced to move, I bought three for the historical record—Disney’s Tron (1982), Saturday Night Live: The Best of Joe Piscopo (1983), and the Kenny Rogers’ film Six-Pack (1982). These choices may seem motivated by the standard-issue ironic detachment haunting post-boomer culture, but I assure you each was selected to maximize the sad connotations of techno-cultural obsolescence. Of the three, Six-Pack may well be the most complex in its layering of melancholia and misery.

Six-Pack on Selecta-Vision is infinitely more depressing than the same film encountered on VHS, Laserdisc, or DVD (if the last object actually exists, God forbid). Perhaps it is a trait unique to media historians, but I’ve always found “extinct” media formats profoundly sad. One can only imagine the original hope invested in these discs as a definitive solution to entropy and thus the key to media immortality. Here was an early attempt to transform the ephemeral experience of the movies quite literally into “records” (the Selecta-Vision system in fact uses a stylus)—the building blocks of an eventual media library. Of course, those who invested in this format were out of luck by 1986, and if they moved over to VHS, they could only watch as a library of videotapes slowly decayed from age and magnetization. Now Blu-Ray is in the process of displacing the DVD (which slayed VHS, obviously) as the new format of eternal transcription—but there really is no end to this anxiety as this obsession with formatting is less about creating a library that might actually outlive its owner than it is about repelling the intruding specter of mortality itself. One has to give credit to the culture industries, which have somehow managed to take a century of wholly disposable media products and invest them with a sense of history, identity, and affect that make millions feel compelled to collect them and repeat—to the grave, apparently—whatever dated pleasures reside within. At this point in history, does anyone who has seen Casablanca (1945) and knows Casablanca really need to own Casablanca? Are episodes of Gilligan’s Island best encountered at random in unexpected moments during the course of life, or are they to be stored on the shelf in “complete seasons,” much like reading-copies of Moby Dick and Ulysses that one keeps on the shelf for a more contemplative rendezvous later in life?

In this respect, owning (and then cataloging and organizing) a body of continually re-formatted films, TV shows, and albums is a ritual that re-affirms the “immortal” flame of one’s taste even as that industrially-inscribed sensibility remains encased in a deteriorating body. As the recent Beatles Box demonstrates, this symptom is particularly pronounced in pop-music fans (myself included), who appear hopelessly caught in a doomed attempt to rekindle whatever feelings of teenage omnipotence have been cathected onto Sgt. Pepper, Exile on Main Street, Never Mind the Bollocks, Nevermind, and whatever other records were considered crucial after I stopped paying attention at the end of the last century. Happily, the Beatles Box may be the last great gesture in this regard as most people under 30 have little to no desire to own music as a material object, having chosen variety and portability over sound fidelity and cover design in circulating the music of the future. Perhaps this will make them less prone to corporatized fetishism, more willing to consume popular texts and then, as with Swiffer pads, be done with them. Already we must celebrate the Net generation’s radical intervention in simply refusing to pay for most mass-produced music, having made the fundamental realization that very few artists are worth shelling out $18.98 (much less the hundreds of dollars needed to replace your copy of Revolver every 15 years). Thrift shelves are now sagging under the weight of discarded CDs—former icons of sonic immortality currently taking their rightful place next to cassettes, 8-tracks, and that most distant and ridiculous of audiophile formats: reel-to-reel tape.

Yes, formats and popular amusements all decay eventually, a process made particularly manifest in the pathos of a Selecta-Vision edition of Six-Pack. Not only is the CED format itself dead, but so too is the cultural imaginary that would produce, enjoy, cherish, and collect a film starring Kenny Rogers. It is a double dead-end of design and desire. For those unfamiliar with Rogers, he first came to prominence in the late ‘60s as the lead singer for Kenny Rogers and the First Edition (“Just Dropped In (to See What Condition My Condition Was In)” was their big hit). He is also known for his 1978 single, “The Gambler,” as well as participating in the landmark “We Are the World” session of 1985 that—at last—brought an end to famine in Africa. At some point he opened a chain of fast-food chicken shacks (Kenny Rogers’ Roasters—most famously a nemesis for Kramer in an episode of Seinfeld). In 1994, a pitcher for the Texas Rangers with the same name threw a perfect game—which no doubt confused many—while in the late ‘90s Rogers became the object of a rather inexplicably brutal series of parodies by Will Sasso on MadTV (see video sidebar). In other words, Rogers is one of those media figures who have proliferated across a range of media (and chicken enterprises) for over forty years—staying within the lexicon of popular reference despite having long ago ceased to generate any cultural product of relevance. Whether we want to or not, we must co-exist in a world that also allows Kenny Rogers inordinate access to mass consciousness, either through music, parody, or poultry distribution.

Six-Pack dates from a period when Rogers—like any efficient proto-convergence franchise--sought to expand beyond the then somewhat limiting domain of country music and capture the larger profits and attention to be found in the movies. The film itself is a confluence of rather unfortunate genres--Smokey the Bandit meets the Bad News Bears—with Rogers playing a NASCAR driver who befriends a motley crew of orphaned children (6 to be exact—hence the title). No doubt this craven calculation in genre/regional hybridization was apparent to many in the period—but with the passing of time, Six Pack becomes an even more pointed reminder of just how low and obvious our expectations are for popular entertainment. Sure, you can say it was a film for kids or the even less demanding audiences that would eventually file into the dinner-theater death compounds of Branson, but that really is no defense at all. If we pretend to befriend the hypothetical viewer who really liked (or likes) Six Pack, that only means we have ceased to struggle against the industry’s vortex of swirling mediocrity--giving up at last on all critical responsibility, holding our noses, and then going down for the last time (perhaps to buy the new Two and a Half Men box-set). Really—and I’m speaking primarily to my fellow media scholars out there—did we put multiple years into a Ph.D. so that we might better understand, defend, and celebrate the pleasures of watching The Ghost Whisperer, having so long ago abandoned any challenge to the world of cynical sentimental crapestry that would create The Ghost Whisperer in the first place?

Six-Pack dates from a period when Rogers—like any efficient proto-convergence franchise--sought to expand beyond the then somewhat limiting domain of country music and capture the larger profits and attention to be found in the movies. The film itself is a confluence of rather unfortunate genres--Smokey the Bandit meets the Bad News Bears—with Rogers playing a NASCAR driver who befriends a motley crew of orphaned children (6 to be exact—hence the title). No doubt this craven calculation in genre/regional hybridization was apparent to many in the period—but with the passing of time, Six Pack becomes an even more pointed reminder of just how low and obvious our expectations are for popular entertainment. Sure, you can say it was a film for kids or the even less demanding audiences that would eventually file into the dinner-theater death compounds of Branson, but that really is no defense at all. If we pretend to befriend the hypothetical viewer who really liked (or likes) Six Pack, that only means we have ceased to struggle against the industry’s vortex of swirling mediocrity--giving up at last on all critical responsibility, holding our noses, and then going down for the last time (perhaps to buy the new Two and a Half Men box-set). Really—and I’m speaking primarily to my fellow media scholars out there—did we put multiple years into a Ph.D. so that we might better understand, defend, and celebrate the pleasures of watching The Ghost Whisperer, having so long ago abandoned any challenge to the world of cynical sentimental crapestry that would create The Ghost Whisperer in the first place?No doubt popular entertainment is always "great" so long as our technologies remain sexy and our tastes remain blissfully unexamined--but lurking behind this joyous proliferation of rat-holes into which to dump our money, time, and attention is the uncomfortable reality evoked by a Kenny Rogers on Selecta-Vision disc (Selecta! --even the name makes you stupider). Like so much other thrift detritus, it is a reminder of objects and affect now utterly drained of all value--maybe eventually even of all ironic value. Such is the destiny of all that is ill-conceived, poorly made, and obscenely ridiculous--be it a Billy Bass Singing-Fish Plaque or the Blu-Ray copies of Norbit that, even now, move inexorably toward their destiny on the future shelves of Goodwill.

Moreover, Six Pack is a reminder that the oft-celebrated move toward media/narrative convergence--beyond opening multiple paths to consumer ecstasy--is just as often (or actually, at the same time) only a guy and his corporation looking to branch out from shit-kicker radio to get a little taste of the Burt Reynolds market--or singing about poker fights he's never been in--or showing up next to Cyndy Lauper at a charity photo-op to keep his profile/brand relevant--or pretending to have expertise in chicken-roasting that he doubtlessly does not possess. And we do nothing about it. Sad, sad indeed.

Moreover, Six Pack is a reminder that the oft-celebrated move toward media/narrative convergence--beyond opening multiple paths to consumer ecstasy--is just as often (or actually, at the same time) only a guy and his corporation looking to branch out from shit-kicker radio to get a little taste of the Burt Reynolds market--or singing about poker fights he's never been in--or showing up next to Cyndy Lauper at a charity photo-op to keep his profile/brand relevant--or pretending to have expertise in chicken-roasting that he doubtlessly does not possess. And we do nothing about it. Sad, sad indeed. For more on Mike Kelley's work, see Mike Kelley. ed. by John C. Welchman, Isabelle Graw, Anthony Vidler. New York: Phaidon Press, 1999.

I am indebted to my more tech-savvy colleague Max Dawson for his knowledge of the Selecta-Vision venture.