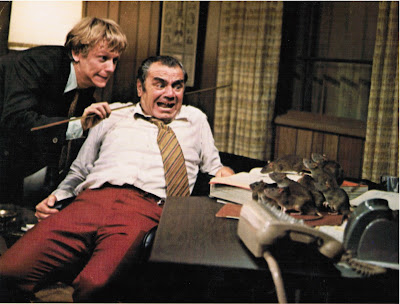

Ernest Borgnine, Menaced by Rats

Soon to be lost forever in the move toward digital effects is the art of appearing menaced by real animals in real time. Before animals actors could be convincingly animated to hit their marks or appear more terrifying, they had to be "wrangled." Human actors, in turn, often had to carry the scene by turning an otherwise harmless tableau of trained animals into blood-curdling terror. In the original Willard (1971), Ernest Borgnine works with a menacing yet relatively manageable octet of rats. One might think Borgnine would be more terrified by Willard himself, his usually timid employee suddenly turned psychopath--but the movie requires us to believe that rats--even just eight of them--are a mortal threat. Note how the rodent co-stars have been cued by a trainer to look, for the most part, out of frame but still in Borgnine's general direction while Borgnine recoils in feigned terror. Given the acceleration of imaging in contemporary horror, this scene, by contrast, appears all the more real and thus all the less terrifying.

Soon to be lost forever in the move toward digital effects is the art of appearing menaced by real animals in real time. Before animals actors could be convincingly animated to hit their marks or appear more terrifying, they had to be "wrangled." Human actors, in turn, often had to carry the scene by turning an otherwise harmless tableau of trained animals into blood-curdling terror. In the original Willard (1971), Ernest Borgnine works with a menacing yet relatively manageable octet of rats. One might think Borgnine would be more terrified by Willard himself, his usually timid employee suddenly turned psychopath--but the movie requires us to believe that rats--even just eight of them--are a mortal threat. Note how the rodent co-stars have been cued by a trainer to look, for the most part, out of frame but still in Borgnine's general direction while Borgnine recoils in feigned terror. Given the acceleration of imaging in contemporary horror, this scene, by contrast, appears all the more real and thus all the less terrifying. This effect is even more pronounced at the lower echelons of filmmaking. Particularly notorious is Ted V. Mikels' The Corpse Grinders (1972) in which domestic cats, having been given a taste of human flesh by unscrupulous catfood makers, begin to turn on their owners for additional meals. While Willard depended for the most part on the mise-en-scene of multiplication (as in, "wow, that's a lot of rats")--The Corpse Grinders combines rudimentary editing tricks and actors struggling to hold/shake cats in such a way that it appears the animal is ripping open the jugular vein. This scene is typical, a young woman undulating on the couch and thrashing her feline co-star back and forth in an attempt to simulate a plausible mutilation. The combination of bad acting, sparse editing, and cheap film stock make for attacks that are more charming than frightful. One also cannot help but empathize with the actors who have been given an almost impossible task here--transforming Puff into a blood-thirsty killer without any effects or image-processing whatsoever.

This effect is even more pronounced at the lower echelons of filmmaking. Particularly notorious is Ted V. Mikels' The Corpse Grinders (1972) in which domestic cats, having been given a taste of human flesh by unscrupulous catfood makers, begin to turn on their owners for additional meals. While Willard depended for the most part on the mise-en-scene of multiplication (as in, "wow, that's a lot of rats")--The Corpse Grinders combines rudimentary editing tricks and actors struggling to hold/shake cats in such a way that it appears the animal is ripping open the jugular vein. This scene is typical, a young woman undulating on the couch and thrashing her feline co-star back and forth in an attempt to simulate a plausible mutilation. The combination of bad acting, sparse editing, and cheap film stock make for attacks that are more charming than frightful. One also cannot help but empathize with the actors who have been given an almost impossible task here--transforming Puff into a blood-thirsty killer without any effects or image-processing whatsoever. Finally, although anyone under the age of 40 may find it incredible, Stephen King was once so popular that Hollywood fought for the right to adapt every single word that came out of his word processor, including a minor effort about a mom and her son trapped in a car by a rabid St. Bernard, the eponymous Cujo (1982). Here we see a third pre-digital strategy for transforming a flesh and fur actor into an object of terror. Unlike the rat-pack stars of Willard or the generally lazy cats of The Corpse Grinders, Cujo the dog could actually act, propelling the film through his formidible talents in barking, growling, and snarling. Make-up helps also--gallons of shaving cream and stage blood rubbed all over his body to transform him from merely rambunctious to plausibly rabid.

Finally, although anyone under the age of 40 may find it incredible, Stephen King was once so popular that Hollywood fought for the right to adapt every single word that came out of his word processor, including a minor effort about a mom and her son trapped in a car by a rabid St. Bernard, the eponymous Cujo (1982). Here we see a third pre-digital strategy for transforming a flesh and fur actor into an object of terror. Unlike the rat-pack stars of Willard or the generally lazy cats of The Corpse Grinders, Cujo the dog could actually act, propelling the film through his formidible talents in barking, growling, and snarling. Make-up helps also--gallons of shaving cream and stage blood rubbed all over his body to transform him from merely rambunctious to plausibly rabid.These attacks would all be done digitally now (as in the 2003 remake of Willard). This doesn't make these older animal attack flicks more "real" or "authentic"--but the lost art of wrangling, blocking, and directing ordinary animals did hold a certain fascination that no longer exists in the cinema--the appreciation of a rather specialized craft shared with varying degrees of competence by the animal, the wrangler, the actor, the director, and the editor.